When Dr. Fitzer wrote the original version of this post in 2016 it was in response to a story told to her by a dear friend but it is a story she has heard over and over in the past four years talking to parents whose children have invisible disabilities. It is a story that hits her hard as a provider, as a parent, and as a person who trains professionals to work with children. If you are a teacher, a school administrator, a paraprofessional, a child study team member, an instructor of afterschool activities- if you interact with children, please read. We beg you.

“Mark is fine. He is social, smart, friendly and full of energy…just a handful.” “You know, he does it because he is a boy.”

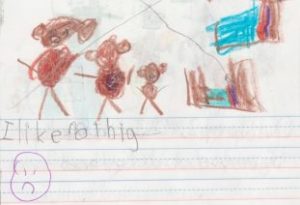

“ Why doesn’t Mark do his writing work in school or do his homework? He is just lazy.” “Mark doesn’t have a disability, he is just manipulative. He acts out to get what he wants or to get out of doing his work” “Mark is playing you with the tantrums and aggression after school when it is time to do homework.” “Marks fears are normal. There is nothing wrong with him. It is just a phase.”

The people who said those things…they were wrong about it being a phase-

And his parents knew it.

After years of hearing similar comments, Mark’s parents finally figured out a system that would lead to a positive outcome for their son. They implemented the system daily, even though it made life harder on them initially, and in the end the results were worth it.

They taught him to independently follow visual to-do lists for his morning and afternoon routines. They tweaked and adjusted. They figured out that crying and aggression during homework disappeared when the afternoon routine included an opportunity right after school for ”free-think time,” a time they didn’t ask him to do much and Mark could choose whatever non-electronic activity he wanted to do. They learned that Mark’s refusal to participate in extra-curricular activities disappeared when they scheduled after school activities earlier in the afternoon instead of in the early evening. They begin teaching behavior relaxation techniques. They felt relief once they learned that Mark actually had a learning disability, and indescribable joy when, after they taught him to use speech-to-text and text-to-speech applications on a computer, he ran to do his homework as soon as he got home from school (“Nope! I don’t need free-think time mom!”).

Combined with consistent reinforcement for using all the supports they put in place, Mark no longer had tantrums and was no longer aggressive. It was also reported that he no longer called himself dumb and stupid. In addition, when many of the supports in place at home were implemented in school, the teacher reported that she saw a huge difference in Mark’s willingness to do work in school. The environmental and instructional supports were not a replacement for instruction. Improving reading, spelling and writing continued to be a top priority, however, the supports in school and at home made it possible for Mark to be behaviorally available for additional instruction.

During this time, Mark was diagnosed with two separate but entangled invisible learning disabilities. An invisible disability is one that cannot be identified based on external physical characteristics or indicators. According to the Invisible Disabilities Association, invisible disabilities include: learning disabilities, anxiety, chronic fatigue, chronic pain, vision and hearing impairments, cognitive disabilities, and brain injury (among others). In Mark’s case, it was dyslexia and an anxiety disorder.

Mark, like other children and adults with invisible disabilities, physically appears just like any other average child. Because invisible disabilities are easy to miss, often times the challenging behavior that accompanies the disability is attributed to “the apple not falling far from the tree,” “parents letting their children get away with murder,” “the child being evil, manipulative or a brat.” (Yes, evil). Since we can’t “see” the disability like we can see an amputated limb or see the evidence of microcephaly, for some reason, it is easier to pass judgement on a parent’s skills or call a child names rather than taking the time to understand and address the behavior.

When a person has an invisible disability, the diagnosis often doesn’t come at birth. Many parents learn that there is a problem after years of teachers telling them that their child “won’t listen, is aggressive, or disrespectful.” Years of unsolicited advice from people who say things like “You need to teach him who is boss.” “They needs discipline.” “Give him stickers on a chart for being good,” or “A good firm hand would fix that up.” Years of doubt, fear, and confusion. In Mark’s case, it took 4 years in school, and years of comments and reward charts that didn’t work, until his parents sought out the right people and received the help they needed to help their son.

It doesn’t need to be that way. There is no reason it has to take so long.

While delayed diagnosis may be inevitable due to the nature of some invisible disabilities, professionals that work with young children and their parents can help by rejecting the pervasive attitude about challenging behavior in otherwise “normal looking” children. You know, the “they will grow out of it,” and the “you need to be firmer” comments. If you are a professional that works with children you can commit to laying a path that leads to earlier identification and earlier intervention. Not only will this help families with children with invisible disabilities, but those with visible disabilities, as well as all families who may need help for myriad reasons. I encourage you to accept the following calls to action and in return I will leave you my direct email address so you can reach out to me if you need help.

I call on you to:

- Have compassion for your students. Your words and actions matter to them. Treat them with kindness. Commit to learning why challenging behavior occurs instead of assuming you know because you think you do.

- Assess what expected skills the most challenging of our children have not mastered, and use evidence-based practices to teach those skills and identify the supports and interventions that will increase the likelihood these students will be successful in school and at home. And if you are unsure how then…

- Attend conferences, webinars, and workshops on academic interventions that actually teach children the skills they need to be successful in school.

- Read more about Direct Instruction and Precision Teaching- it isn’t enough to teach most of the children in your classroom, make sure you have the skills to teach all of the children in your classroom. (Check our our recently published list which is a great starting point for your reading).

- Attend workshops on human behavior, classroom management, positive behavior supports/antecedent interventions presented by professionals who experts in working with kids with ADHD and/or learning disability diagnoses and in the science of human behavior.

- Treat parents with respect. Be kind and patient with them, and help direct them toward evidence-based practices and away from pseudoscientific treatment fads.

- Stop using the phrase “The apple doesn’t far from the tree” when you are chuckling about a parent’s struggle with your colleagues. Actually stop chuckling when you are talking about a parent’s struggle and practice compassion.

- Raise your expectations for anyone with a disability and embrace every child as ever deserving of an independent and fulfilling life.

I call on you, no matter who you are, or what your chosen profession is, to remove the invisible disability cloak.

Adrienne Fitzer, PhD, BCBA, started working with students with autism in the Washington, D.C. area 20 years ago as an undergraduate majoring in psychology at the University of Maryland. After graduating Phi Beta Kappa, she continued working in the field and attended the Learning Processes Sub-Doctoral Program in Psychology at the Graduate Center and Queens College of the City University of New York. She holds a Masters Degree from Queens College in Psychology, was all but dissertation (ABD) in 2008 and went back to school in 2017 to complete her doctorate. In 2021, Dr. Fitzer (finally) earned her PhD from the Graduate Center, City University of New York in Psychology with an emphasis on human learning.

Adrienne Fitzer, PhD, BCBA, started working with students with autism in the Washington, D.C. area 20 years ago as an undergraduate majoring in psychology at the University of Maryland. After graduating Phi Beta Kappa, she continued working in the field and attended the Learning Processes Sub-Doctoral Program in Psychology at the Graduate Center and Queens College of the City University of New York. She holds a Masters Degree from Queens College in Psychology, was all but dissertation (ABD) in 2008 and went back to school in 2017 to complete her doctorate. In 2021, Dr. Fitzer (finally) earned her PhD from the Graduate Center, City University of New York in Psychology with an emphasis on human learning.

Dr. Fitzer has co-edited two books on ABA and Autism, Autism Spectrum Disorders: Applied Behavior Analysis, Evidence and Practice (2007, 2013) and Language and Autism: Applied Behavior Analysis, Evidence and Practice (2009). Her research is published in the Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior and she has presented on behavior analysis at conferences and workshops. Most recently, she completed her dissertation titled “An evaluation of an application designed for the iPad to measure stimulus overselectivity for future use in autism research.”

From 2006-2012, Adrienne Fitzer provided quality applied behavior analysis services to children with autism in public schools. In 2011, Dr. Fitzer realized that she could combine her passion for teaching applied behavior analysis and working with those who care for and work with learners with autism and related disorders by focusing on parent and professional training. She opened The Applied Behavior Analysis Center (ABAC) in 2013 to achieve that professional dream.

As ABAC has grown into an online education center, Adrienne has grown with it, finding that she has never loved a job more as it has provided her the opportunity to raise her children, broaden her scope of competence, finish school, and give back to the community. You can often find her sitting on her porch or in front of a warm toasty fireplace working, making new friends and learning from colleagues around the world, and writing for the ABAC Blog on ethics, small business ownership, self-management and self-acceptance.